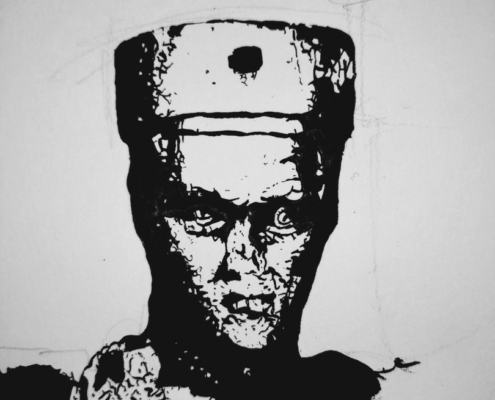

“Brotherly Love”, Alexandre Mitchell, 2023 (42 x 59cm, Indian ink)

This drawing expresses the long and tumultuous relationship between Venice and Constantinople throughout the Middle Ages. These two great Christian cities were also two poles of Christianity, Latin ‘Catholic’ and Greek ‘Orthodox’.

Their exchanges came to an abrupt end in 1204 when Venice conspired to divert the Fourth Crusade from the Holy Land so that it could attack Constantinople and sack the City.

The Fourth Crusade was the first international massacre of Christians by other Christians on a holy quest. How could this have happened at a time when religious fervour was particularly strong among Christians?

The Latin crusaders put forward various specious arguments to justify their massacre of Greek Orthodox Christians and some Venetians of the time justified their involvement in these affairs by stating that they were simply trying to help the former Byzantine emperor Alexius and that everything had gone wrong. It is more likely that fraternal relations between the cities and Christians of different denominations were overshadowed by more practical considerations.

Although Venice was Christian and respected the spiritual supremacy of the Pope in Rome – it was Pope Innocent III who had spearheaded the Fourth Crusade – the Venetians were pragmatic merchants, constantly negotiating their position in an ever-changing Mediterranean world. Rather than seeing 1204 as a colossal disaster among Christians, perhaps we should see it as the inevitable culmination of Venice’s economic and geopolitical ambitions.

Pope John Paul II apologised for this horrific event in a famous speech on May 4, 2001 to the chief representative of the Greek orthodox church:

(…) Some memories are especially painful, and some events of the distant past have left deep wounds in the minds and hearts of people to this day. I am thinking of the disastrous sack of the imperial city of Constantinople, which was for so long the bastion of Christianity in the East. It is tragic that the assailants, who had set out to secure free access for Christians to the Holy Land, turned against their own brothers in the faith. The fact that they were Latin Christians fills Catholics with deep regret. (…)

Many precious objects, as well as thousands of columns and building materials, were shipped to Venice. Most of them can still be seen today in Venice’s urban landscape. One of these plundered objects is a sculpted group known as the Tetrarchs, set into the corner of the façade of St Mark’s Basilica. It depicts two pairs of Roman rulers embracing, hence the name Tetrarchs (‘Four Rulers’). According to an ancient Byzantine text, a similar sculpted group stood in a public square in Constantinople called Philadelphion. And ‘Philadelphion’ in Greek… means ‘brotherly love’.

It may or may not have been the same monument, but the way in which the Tetrarchs were stolen from Constantinople and incorporated into the very façade of a prominent building in Venice is symbolic of a doomed relationship between the two cities. This is why the two fraternal sovereigns are shown drowning in the Grand Canal, blocked by a chain attached to Ca’ da Mosto, the oldest Palazzo on the Grand Canal, decorated in a Venetian-Byzantine style.

This chain is reminiscent of two historic giant metal chains. Doge Pietro Tribuno set up a chain at the entrance to the Grand Canal in 906 CE to prevent enemy fleets from entering the heart of Venice. This chain was inspired by a far more famous chain, that of the port of Constantinople, which protected it from enemy fleets for 700 years, until 1453, when the chain was circumvented by Mehmet II’s Ottoman forces.

Just as the Tetrarchs were displayed on the façade of the Basilica of San Marco after 1204, the chain is now on display in the Istanbul Museum of Archaeology. Even though 600 years have passed since 1453, the chain is still a reminder of the fall of the largest city in the eastern Mediterranean.

Further reading

Tetrarchs and re-used materials

- Ludovico Rebaudo, “Il gruppo dei tetrarchi: una lettura del reimpiego”, in Giuseppe Cuscito (ed.), Riuso di monumenti e reimpiego di materiali antichi in età postclassica: il caso della Venetia, Trieste, Editreg, 2012, p. 147-158.

- Spolia | for a full bibliography and current research on the topic of decorative sculpture reused in new monuments, see DiSpLay (Digital Spolia Layering), the ongoing scientific project at the university of Venice | wikipedia

- Tetrarchy | online

- Monument of the Tetrarchs | online

Fourth Crusade (primary sources)

- de Villehardouin, Geoffrey. “Chronicle of The Fourth Crusade and The Conquest of Constantinople” | online

- Robert of Clari. “The Conquest of Constantinople” | online

Fourth Crusade (secondary sources)

- “The Fourth Crusade and the Latin empire of Constantinople”, 2006 | Encyclopædia Britannica

- The fourth Crusade | Wikipedia

- The Sack of Constantinople | Wikipedia

- Angold, Michael, “The road to 1204, the Byzantine background to the Fourth Crusade”, Journal of Medieval History, Vol. 25/3, 1999, pp. 257–278.

- Bartlett, W. B., An Ungodly War: The Sack of Constantinople and the Fourth Crusade. Stroud: Sutton Publishing, 2000.

- Harris, Jonathan, Byzantium and the Crusades, Bloomsbury, 2nd ed., 2014.

- Kazhdan, Alexander “Latins and Franks in Byzantium”, in Angeliki E. Laiou and Roy Parviz Mottahedeh (eds.), The Crusades from the Perspective of Byzantium and the Muslim World. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks, 2001, pp. 83–100.

- Kolbaba, Tia M. “Byzantine Perceptions of Latin Religious ‘Errors’: Themes and Changes from 850 to 1350”, in Angeliki E. Laiou and Roy Parviz Mottahedeh (eds.), The Crusades from the Perspective of Byzantium and the Muslim World Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks, 2001, pp. 117–143.

- Hodgson, Natasha, “Honour, Shame and the Fourth Crusade”, Journal of Medieval History, 39/2, 2013, pp. 220-239.

- Lester, Anne E., “What remains_ women, relics and remembrance in the aftermath of the Fourth Crusade”, Journal of Medieval History, 40/3, 2014, pp. 311-328.

- Madden, Thomas F., Enrico Dandolo and the Rise of Venice, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003.

- Madden, Thomas F., and Donald E. Queller, The Fourth Crusade: The Conquest of Constantinople. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1997.

- Noble, Peter, “The importance of Old French chronicles as historical sources of the Fourth Crusade and the early Latin Empire of Constantinople”, Journal of Medieval History 27, 2001, pp. 399–416.

The chain in Venice and in Constantinople

- Venice on foot | online

- Georgios Anapniotis, The truth about the great chain of the golden horn | ResearchGate

- Takeno, J., Takeno, Y., “The Mystery of the Defense Chain Mechanism of Constantinople”, in Koetsier, T., Ceccarelli, M. (eds.) Explorations in the History of Machines and Mechanisms. History of Mechanism and Machine Science, vol 15. Springer, Dordrecht. 2012 | doi

- Navigation barriers | wikipedia

- Golden Horn Chain | atlasobscura | ancient-origins

Palazzo Ca’ da Mosto

- Palazzo Ca’ da Mosto | wikipedia

- La famiglia e il palazzo Da Mosto | Conoscerevenezia

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank Dr Marcella De Paoli (curator of Venice’s museum of archaeology) and Dr Myriam Pilutti Namer (Ca Foscari University of Venice and member of the DiSpLay research project) for a wonderful personal guided tour of the collections of the museum of archaeology in Venice and a very learned conversation on the ancient Byzantine spolia found in Venice.